In the past 40 years the Church has increasingly expressed concern about the care and preservation of the environment. This concern was first articulated by Pope Paul VI in an apostolic letter written in 1971 marking the 80th anniversary of Rerum Novarum (which is Latin for “About New Things”). He said that humanity is becoming more aware of its ‘ill-considered exploitation of nature” and that we risk destroying it and becoming victims of this degradation.

This cause was re-asserted by Pope John Paul II, and even more so infrequent statements made by Pope Benedict XVI. “If you want to cultivate peace, protect creation.” (World Day of Peace, January 1, 2010. And in Benin, Africa, in 2012, he said “creation is the beginning and the foundation of all God’s works, and its preservation has now become essential for the peaceful co-existence of humankind.”

Pope Francis has written an encyclical in 2015, Laudato Si, and notes “the ecological crisis is a summons to profound interior conversion … and ecological conversion.” (LS217) Watch videotapes exploring Pope Francis’ encyclical, in depth, here.

But the Church’s concern for the preservation of creation and fears about its exploitation was not always so clear and forthright. One of the major reasons is that since the time of the Reformation in the 16th century, the Church’s primary focus was on questions pertaining to the relationship between God and humankind, e.g. “What does it mean to be saved?” What is the relationship between faith and good words?” “What must I do to merit eternal life?” These took center stage. The role of the created world was not abandoned, but it was neglected.

Science without religion is weak; religion without science is blind.

Albert Einstein

Then too, with the advance of scientific observation, people like Copernicus and Galileo were probing the heavens with a newly-developed instrument called the “telescope.” Their finds revealed that the Earth was not the center of the universe but merely one of the planets revolving around the sun.

To Church authorities of that time, such a proposition was unacceptable, even bordering on heresy. In the 19th century, Charles Darwin proposed that in the evolution of the universe, all species of life evolved through a process of natural selection, not by a special creation of God. The Church rejected his thesis because it seemed to deny God’s providence and also appeared to be inconsistent with the biblical account of creation as found in the book of Genesis. Science appeared to have trumped Church teaching; a long period of mutual suspicion and defensiveness ensued.

Since the middle of the 20th century, major advances in space technology, astronomy, evolutionary biology, and physics have yielded new information regarding the origins of the universe its ongoing expansion, and evolutionary enfolding toward greater complexity and unity. In light of these developments, scholars from both sides have begun to recognize the value of dialogue, as long as the goals and principles of both are respected. Religious scholars are recognizing new ways of speaking about God’s ongoing, dynamic spirit in creation, the evolution toward greater communion on all levels, and the incredible network of relationships that make up Mother Earth.

To recognize how the human species is inter-connected with the created world and how dependent we are on it for our continued life and existence is recognizing an astounding truth. For example, take a reflective walk through any supermarket and begin asking yourself where each product comes from (e.g., the bread, cheese, spaghetti, vegetables meat, fish, ice cream, etc.). Then ask yourself how many people are involved in bringing all those products to the shelves of the supermarkets (e.g., farmers, ranchers, fisher people, harvesters, truck drivers, packagers, grocers, shelf stockers, etc.), then you begin seeing in a very small way how interconnected we are with creation around us.

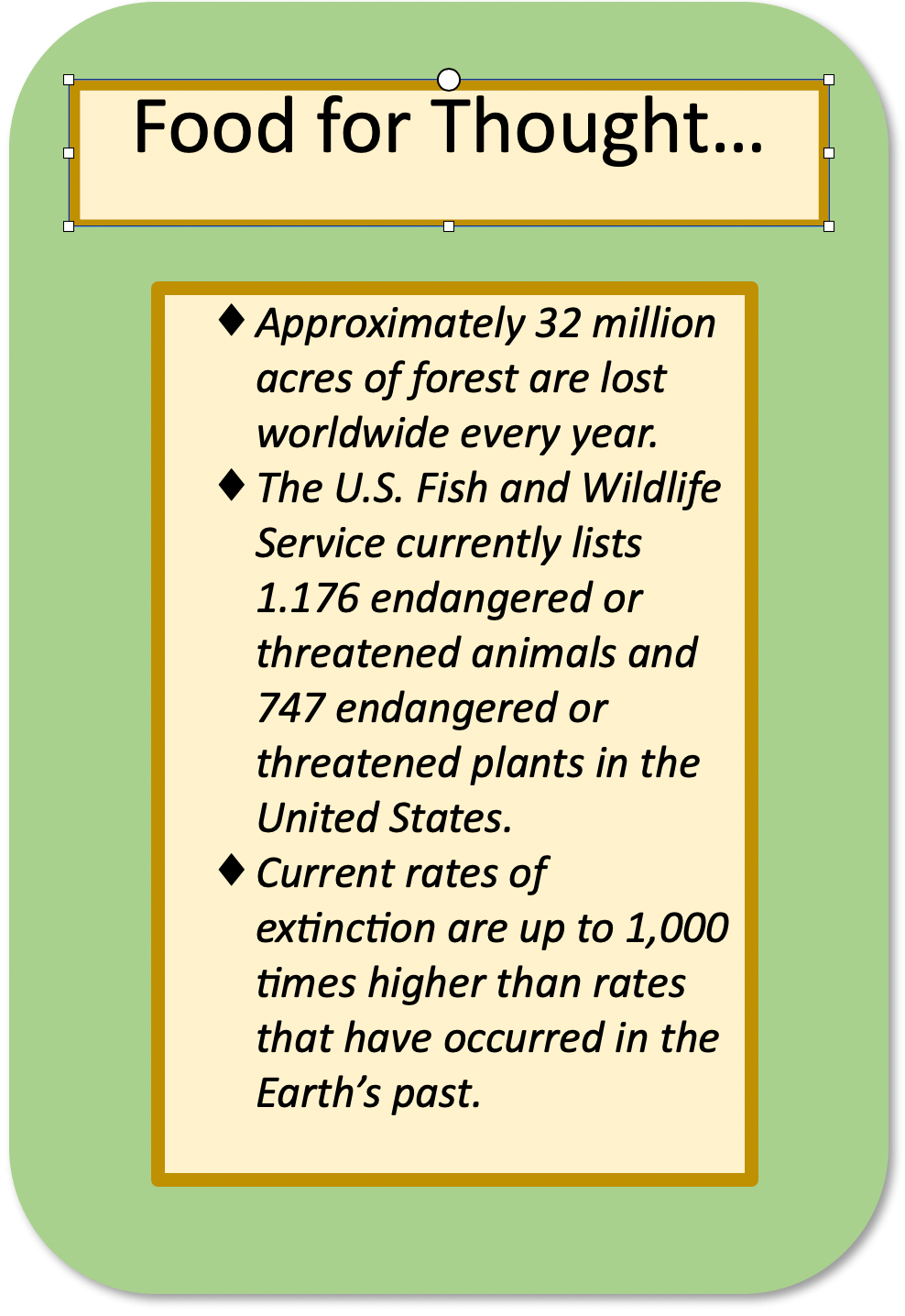

A major area of possible fruitful dialogue between science and religion comes from the mutual concern about the abuse and destruction of countless species and other vital resources of the created world. Unless representatives from both sides come together in common effort to provide information, data, and support for preserving the environment, we will endanger the promise of future sustainable resources for our children and grandchildren and the children and grandchildren of all living species.

It is also becoming clear that the lack of respect for life extending to all forms of creation is almost always to the detriment of the poor, the powerless, and the disenfranchised. They bear the major brunt of our environmental destruction. The Church must speak out on these issues which are religious and frequently moral and ethical. Now it is clear to most scientist and to the Church that human activity is severely damaging our environment – air, land, water, living organisms of various kinds, and animal life – and this degradation is having a profound effect on human life, especially those living in poor communities throughout the world.

Questions for Discussion:

1. Is the Church a key player in the environmental movement today? Should it be?

2. Do you think the issue of the “environment” has become too political and polarized in our times?

3. What do you think are the primary environmental issues that the Church should raise up to the consciousness of the faithful?